When the Capital was Silenced: Delhi Politics, Democracy, and the Assault on Federalism

- Jagneet Singh

- 2 days ago

- 6 min read

The enactment of the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi (Amendment) Act, 2023 represents one of the most serious constitutional confrontations in contemporary India, not because it concerns the technical administration of civil services, but because it fundamentally reorders the relationship between the citizen, the state, and the Constitution. At its core, the law raises a question that constitutional democracies cannot afford to evade: can the will of the electorate be overridden through ordinary legislation when it becomes politically inconvenient?

On 11 May 2023, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court of India delivered what appeared to be a definitive resolution to the long-standing dispute between the Union and the elected government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi. Interpreting Article 239AA purposively, the Court held that, save for public order, police, and land, legislative and executive control over services in Delhi vests in the elected government. The judgment was not merely an exercise in textual interpretation; it was an affirmation of democratic constitutionalism. The Court emphasised that representative government is rendered meaningless if those chosen by the people are denied control over the machinery required to govern. Civil servants, the Bench noted, are bound by a “triple chain of accountability”, to ministers, to the legislature, and ultimately to the people.

The Union government’s response was swift and revealing. Within days, it promulgated an ordinance that effectively neutralised the judgment, later replacing it with the Delhi Services Act, 2023. This legislative manoeuvre was not an attempt to clarify constitutional ambiguity but a direct assertion of political supremacy over judicial interpretation. In doing so, the Union converted what was a constitutional settlement into an institutional standoff, signalling that electoral legitimacy and judicial authority would yield to central control when the two conflicted. The speed and substance of this response suggest that the law was driven less by administrative necessity and more by political unwillingness to accept judicial reaffirmation of democratic authority.

The architecture of the 2023 Act exposes its constitutional character with troubling clarity. By creating the National Capital Civil Service Authority and vesting decisive power in the Lieutenant Governor, the law ensures that unelected officials can outvote the Chief Minister of Delhi on matters central to governance. This structure does not merely dilute executive authority; it inverts democratic hierarchy. Ministers remain politically accountable for governance outcomes while being institutionally denied control over the bureaucracy tasked with implementation. Such an arrangement violates not only the spirit of Article 239AA but also the foundational democratic principle that responsibility must accompany power.

The constitutional injury inflicted by this law is not abstract. It is borne directly by the electorate of Delhi. Citizens participated in free and fair elections, chose a government, and entrusted it with governing the city. That mandate has now been hollowed out. Regardless of political affiliation, whether one supports the Aam Aadmi Party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Congress, or any other political formation—the effect is the same: the vote has been stripped of its substantive value. Democracy, reduced to a procedural ritual without consequence, ceases to be democracy in any meaningful sense.

Proponents of the law have attempted to justify it by invoking allegations of corruption and administrative incompetence against the elected government of Delhi. This justification is constitutionally untenable. The Indian constitutional framework already provides mechanisms to address corruption, independent investigative agencies, judicial scrutiny, and electoral accountability. What it does not permit is pre-emptive disenfranchisement. Parliament is not constitutionally authorised to suspend self-governance because it distrusts the political choices of citizens. To do so is to arrogate to itself the role of judge and jury, undermining both popular sovereignty and the separation of powers.

Equally alarming is the precedent the Act establishes. Through an ordinary statute, Parliament has effectively rewritten the operational meaning of Article 239AA without undertaking a constitutional amendment. This manoeuvre collapses the distinction between constituent power and legislative power. If such practices are normalised, no constitutional arrangement remains secure. Today it is Delhi; tomorrow it could be any opposition-ruled state. Federalism, already strained by fiscal and administrative centralisation, becomes increasingly conditional and politically contingent.

Delhi’s status as the national capital does not justify this erosion. On the contrary, it heightens the constitutional stakes. Delhi is not merely an administrative unit; it is a demographic and political microcosm of India. Residents from every state live and work within its boundaries. An assault on Delhi’s democratic rights therefore reverberates nationally. If the capital of the world’s largest democracy cannot enjoy a fully functional elected government, the promise of federal self-rule elsewhere becomes increasingly illusory.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah has argued that leaders such as Nehru and Ambedkar were opposed to granting full statehood to Delhi. Even if one were to accept this historical claim, constitutional interpretation cannot be frozen in the socio-demographic conditions of the 1950s. At the time, Delhi’s population was under a million. Today it exceeds twenty-five million, surrounded by sprawling satellite cities such as Gurgaon and Noida, forming one of the most complex urban agglomerations in the world. Constitutional governance must respond to lived realities, not selectively invoked historical intent.

The consequences of the Services Act have already manifested in administrative paralysis. The second tenure of the elected Aam Aadmi Party government has been marked by stalled decision-making, delayed postings, and bureaucratic vetoes. Governance has been structurally engineered to fail, producing a perverse situation in which an elected government bears political responsibility without possessing governing authority. This is not cooperative federalism; it is coercive centralism.

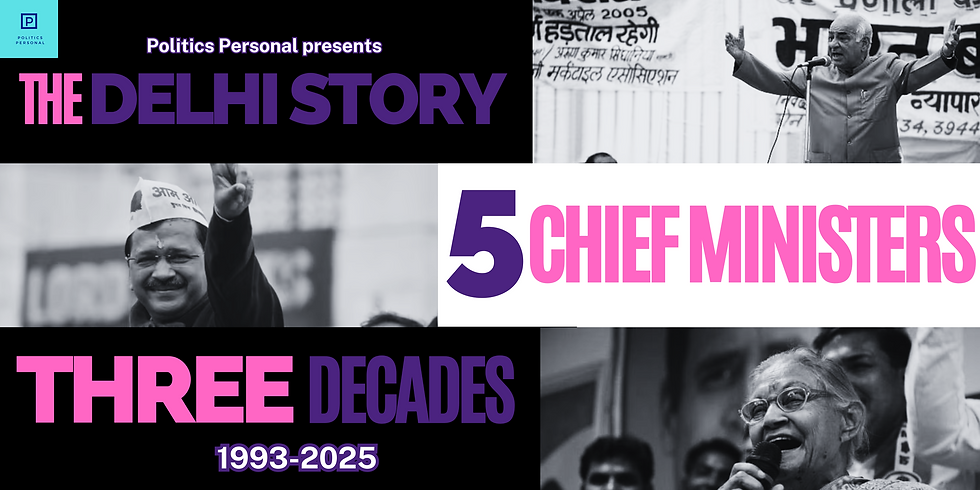

The political implications of this constitutional distortion become clearer when viewed through Delhi’s electoral history. For nearly fifteen years, Delhi was governed by the Congress while the Union government was also led by the Congress. During this period, the concentration of administrative authority in the Centre did not provoke constitutional crisis because electoral alignment masked structural imbalance. The same constitutional framework continued when power at the Centre shifted to the BJP. However, the decisive rise of the Aam Aadmi Party disrupted this equilibrium. For the first time, Delhi elected a government that was both electorally dominant and politically adversarial to the Centre.

What followed was not merely political friction but institutional recalibration. The very administrative arrangements that had earlier enabled Congress-led governance, and later BJP-led central influence, were reasserted and reinforced once they became tools to constrain an electorally ascendant AAP. The Delhi Services Act, 2023 must therefore be understood not as an isolated legal reform, but as the culmination of a long-standing structural asymmetry, now hardened into statute to ensure that electoral transition does not translate into real power transfer.

By stripping the elected AAP government of effective authority while retaining its formal responsibility, the law enables a de facto transition of power without a de jure change in government. It allows the BJP-led Union executive to exercise decisive control over Delhi’s administration without contesting or winning a mandate from Delhi’s voters. This represents a deeply troubling development in constitutional practice: political change achieved through institutional displacement rather than democratic competition.

Such a model, if normalised, carries implications far beyond Delhi. It establishes a template through which opposition governments can be neutralised not by defeating them at the ballot box, but by hollowing out their authority through statutory design. Today, it is AAP in Delhi; tomorrow, it could be any regional party governing a politically inconvenient territory. Democracy is not formally suspended, but functionally bypassed. Elections continue, governments are sworn in, yet real power migrates elsewhere.

The silence or strategic acquiescence of certain regional parties that enabled the passage of this law only compounds the constitutional harm. Their short-term political calculations overlook the long-term consequences of federal erosion. The warning articulated by Martin Niemöller remains painfully relevant: constitutional injustice thrives when resistance is selective.

Ultimately, the Delhi Services Act weakens the constitutional order by severing the link between the electorate and governance. It transforms citizens into spectators, watching their democratic choice rendered ineffective by legislative design. This is not merely a dispute between the Centre and a territorial government; it is a test of India’s commitment to constitutional democracy itself. The Supreme Court’s judgment of May 2023 reaffirmed a simple yet profound principle: in a democracy, power must flow from the people. The legislative response sought to reverse that flow.

The question that remains is not whether one supports the Congress, the BJP, or the Aam Aadmi Party, but whether Indians are willing to accept a constitutional order in which governments can be changed in effect without being changed in fact. When electoral verdicts no longer determine who governs, democracy becomes conditional, fragile, and reversible. The Constitution does not belong to any party, and neither does Delhi. In defending Delhi’s right to self-government, one is defending the constitutional promise that authority in India ultimately derives from the people, and not from legislative or bureaucratic mechanisms designed to bypass them.

Comments