Between Homeland and History: An Analysis of the Israel–Palestine Conflict from the Ottoman Era to Today

- Jagneet Singh

- Dec 7, 2025

- 7 min read

The Israel–Palestine conflict is often described as one of the world’s most intractable struggles. Yet behind the slogans, headlines, and diplomatic deadlocks lie two deeply human stories, stories of survival, belonging, fear, and aspiration. Understanding this conflict requires more than recounting wars; it requires analysing how political structures, national identities, colonial decisions, and security dilemmas evolved over time. This article, combining a political-science lens with humanised narrative, traces the conflict from its roots in the late Ottoman period to the complexities of the present.

I. Life Before Nationalism: Ottoman Palestine as a Shared Space

Before the late 19th century, Palestine was not a battleground of competing nations but part of the Ottoman Empire, governed through a decentralised system where villages and cities managed their own affairs. Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived in close proximity in towns like Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias, and Safed.

Political-science scholars describe this period as one of pre-national coexistence, where identity was shaped not by nationalism, but by religion, locality, and family networks. Jews, though a minority, were embedded in the social fabric of the region, and the idea of a Jewish state had not yet materialised.

This world would transform rapidly with the rise of modern nationalism, a European export that would take root among both Jews and Arabs and ultimately reshape the political destiny of Palestine.

II. The Rise of Zionism and Palestinian Nationalism: Competing Dreams on Shared Land

Zionism: A National Movement Born from Trauma and Hope

In the late 19th century, European Jews faced rising antisemitism, pogroms, and exclusion. Many felt insecure in societies that increasingly defined belonging through ethnic nationalism. Out of this insecurity emerged Zionism, led by Theodor Herzl, advocating for a Jewish homeland to ensure safety and dignity.

Though Zionism was political, its emotional foundation was profound. It combined the longing for ancestral land with the urgent need for collective protection. Early Jewish migrants arrived in Palestine seeking refuge and revival, purchasing land and forming agricultural communes (kibbutzim). To them, this was national rebirth after centuries of exile.

Palestinian Arab Nationalism: Protection of Land, Identity, and Majority Status

At the same time, Palestine’s Arab population, overwhelmingly the majority, began developing political consciousness shaped by:

attachment to land and ancestral villages,

the wider Arab cultural awakening (Nahda),

fear of losing demographic control to organised immigration.

Palestinian nationalism emerged not as rejection of Jewish religious presence, but as a response to the political project of Zionism, which appeared increasingly state-like and expansionary.

The stage was set: two national movements, not inherently enemies, but inevitably in conflict over territorial sovereignty.

III. World War I and the British Mandate: The Crucible of Conflict

World War I shattered the Ottoman Empire and opened the Middle East to British influence. Britain issued contradictory promises that would trap Jews and Arabs in a web of political confusion

To Arab leaders (Hussein–McMahon correspondence), Britain promised independence, including Palestine, in exchange for a revolt against the Ottomans.

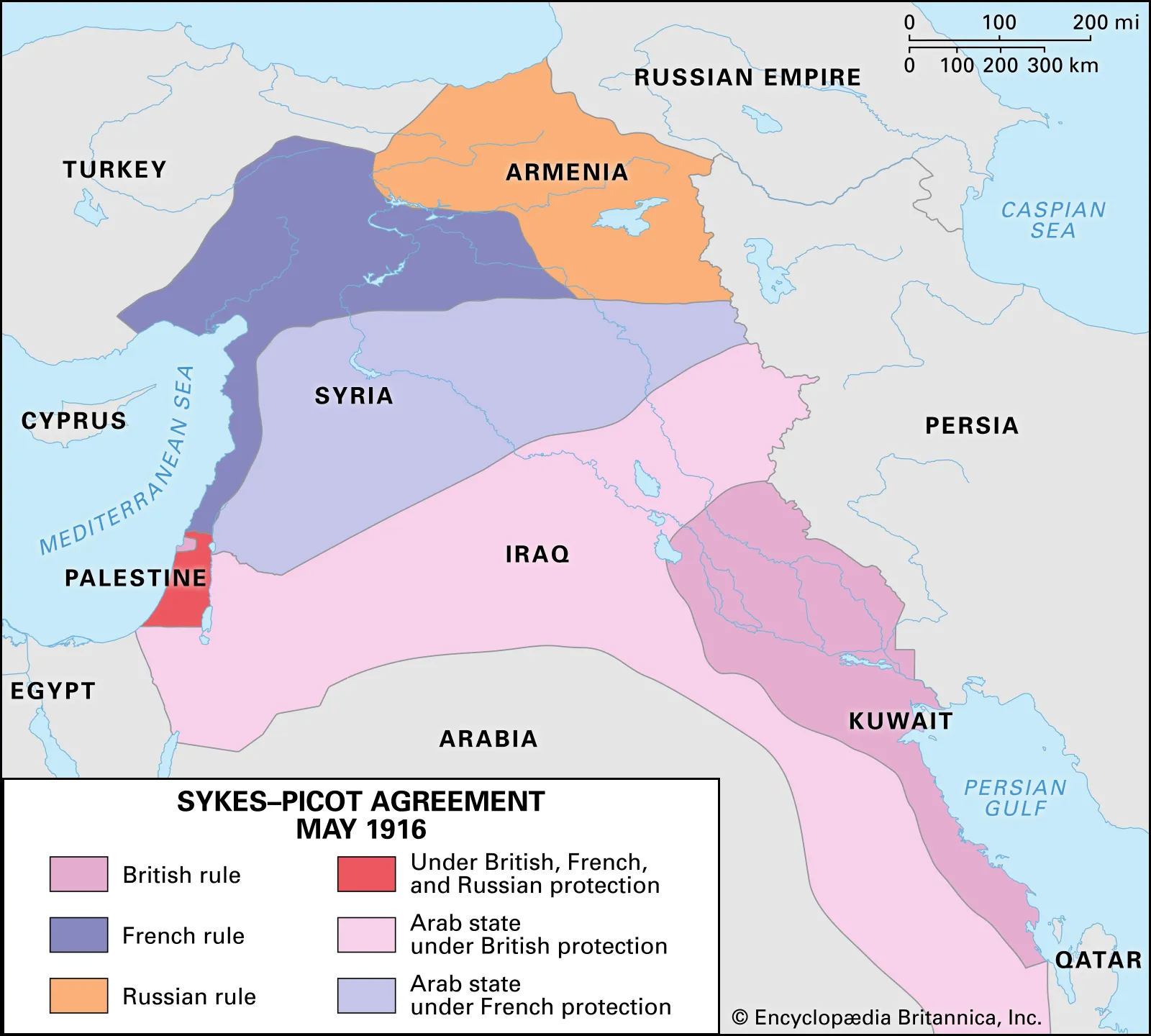

To France (Sykes–Picot Agreement), Britain agreed to divide the region into colonial zones.

To the Zionist movement (Balfour Declaration, 1917), it pledged support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine.

Political science views this as imperial strategic ambiguity, Britain maximised wartime advantage without resolving inherent contradictions. But for Jews and Palestinians, these promises created incompatible expectations that would shape decades of mistrust.

British Mandate (1920–1947): Institution Building vs. Fragmentation

Under British rule, Jewish immigration rose sharply, especially as European antisemitism intensified. The Zionist movement developed state-like institutions, the Jewish Agency, militias (Haganah), schools, financial networks, and became increasingly prepared for independence.

Palestinians, meanwhile, experienced political fragmentation due to British repression, internal rivalries, and lack of external support. Land sales to Zionist groups created displacement anxieties. Tensions escalated, erupting into the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939, which Britain suppressed brutally.

Political science identifies this period as one of asymmetric state-building: one side gained organisational capacity; the other was actively weakened.

IV. The Holocaust and Moral Urgency: A Global Turning Point

The Holocaust fundamentally changed international attitudes. Six million Jews were murdered, and survivors found borders closed as they sought refuge. The world’s conscience shifted sharply: the idea of a Jewish homeland gained legitimacy not only as a political demand but as a moral necessity.

For Palestinians, however, this moment carried a painful irony. While empathising with Jewish suffering, they questioned why they had to bear the consequences of European crimes. Two traumas now stood face to face:

The Jewish trauma of extermination

The Palestinian trauma of feared displacement

The inability of international diplomacy to reconcile these emotional realities set the stage for the conflict’s next phase.

V. 1947 Partition and the 1948 War: Two Births, One Catastrophe

In 1947, the United Nations proposed the Partition Plan, dividing Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. Jews, seeing a path to sovereignty, accepted it. Palestinians rejected it on grounds of demographic injustice: they were the majority population yet allocated less land, much of it already containing Arab villages.

War erupted. When Israel declared independence in May 1948, neighbouring Arab states intervened. The war ended with Israel controlling 78% of the territory, more than the UN plan had granted. For Israelis, 1948 was liberation, the rebirth of a nation ending centuries of vulnerability. For Palestinians, it was the Nakba, the catastrophe, marked by the displacement of around 750,000 people and the destruction of over 400 villages.

Political science interprets 1948 as a foundational rupture: the creation of a new state without a parallel creation of a Palestinian state, producing a chronic imbalance that still shapes the conflict today.

VI. The 1967 War and the Occupation: The Conflict’s Deep Structure Takes Shape

The next major turning point came with the Six-Day War in 1967, when Israel captured:

the West Bank

Gaza Strip

East Jerusalem

Sinai Peninsula

Golan Heights

This transformed the conflict from a dispute between states into an occupation involving millions of Palestinians. Israel now controlled territories central to Palestinian identity and future statehood.

Political science uses the term “protracted occupation”, which generates cycles of resistance, repression, negotiation, and stalemate. Israel began establishing settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, initially strategic, later ideological. Palestinians, meanwhile, reorganised under the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), seeking international recognition.

By the 1970s, the PLO’s identity shifted from revolutionary guerrilla movement to diplomatic actor. The 1974 UN resolution recognizing Palestinians as a people with the right to self-determination was a milestone.

VII. Intifadas and Oslo: Hope, Breakdown, and Disillusionment

First Intifada (1987–1993)

The First Intifada was a mass grassroots uprising driven by frustration with occupation. It featured civil disobedience, strikes, and protests. The Israeli response was forceful, attracting global attention to Palestinian suffering. The uprising created political pressure for negotiations.

Oslo Accords (1993–1995)

In 1993, Israel and the PLO recognized each other and established the Palestinian Authority (PA) for limited self-governance. Oslo generated immense hope. Yet its ambiguities, especially on settlements, borders, Jerusalem, and refugees, made it fragile. Extremists on both sides opposed compromise. The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 shattered the peace camp in Israel.

Second Intifada (2000–2005)

Triggered by political stalemates and provocations, the Second Intifada became far more violent. Suicide bombings, military operations, and the construction of the separation barrier deepened mistrust. Oslo effectively collapsed, replaced by hardened identities and physical separation.

VIII. Division, Stagnation, and New Geopolitics in the 21st Century

In 2006, Hamas won elections, creating a split between Hamas (Gaza) and Fatah (West Bank). Internal Palestinian political division weakened diplomatic leverage. Meanwhile, Israel shifted politically rightward, accelerating settlement expansion that fragmented the West Bank.

Gaza became a focal point of suffering. After Hamas took control in 2007, Israel and Egypt imposed a blockade. Multiple wars devastated the strip, creating severe humanitarian crises.

At the same time, the Abraham Accords (2020) showed that Arab states were willing to normalise relations with Israel without resolving the Palestinian issue, reflecting changing regional priorities.

IX. The Post-2023 Landscape: Escalation, Trauma, and an Uncertain Future

The 2023 Hamas attack and the massive Israeli military response marked one of the most devastating chapters in the conflict. For Israelis, the attack represented an existential security breach. For Palestinians, especially in Gaza, the humanitarian cost reached unprecedented levels. International debates on war crimes, proportionality, and blockade intensified.

Political science categorises this phase as a “high-intensity asymmetrical conflict”, driven by:

shifting regional alliances

weakening international consensus

polarised domestic politics

deepening humanitarian concerns

The conflict today remains shaped by unresolved core questions:

What are the final borders?

What happens to the settlements?

What is the status of Jerusalem?

How are refugees compensated or repatriated?

Can Palestinian political leadership reunify?

Can Israel guarantee security without perpetual occupation?

No durable solution can emerge without addressing these interlinked dilemmas.

Conclusion: A Conflict of Memory, Identity, and Power

The Israel–Palestine conflict is more than a territorial dispute; it is a confrontation between two national stories, each rooted in trauma, longing, and historical consciousness. Political-science analysis shows that the conflict persists due to asymmetric power, competing nationalisms, colonial legacies, and institutional weaknesses. But the human side reveals something deeper: two peoples convinced that their survival depends on control of the same land.

For Israelis, the state is a shield against a long history of persecution.For Palestinians, the land is their heritage, identity, and right to self-determination. The tragedy is not that both sides have strong claims, but that those claims have unfolded through war, displacement, occupation, and fear. The challenge for the future is not simply diplomatic but emotional: recognising that neither people can be erased, and neither can be fully safe or free without the dignity and security of the other.

Peace, if it ever arrives, will not be achieved by perfect plans but by acknowledging imperfect histories, and building a shared future from the painful but undeniable truth that both peoples belong to the same land in different yet legitimate ways.

Very insightful! This is a very well researched article and is successful in creating a spark in the reader! Although the '7 minute read' claim did not work for me (took me around 15 minutes) But the article was great!!